Belladonna of Sadness Hindi Subbed [Full Movie] | Kanashimi no Belladonna Hindi Sub!!

Kanashimi no Belladonna

Belladonna of SadnessSynopsis

The beautiful peasant woman Jeanne is raped by a demonic overlord on her wedding night. Spurned by her husband, she has no outlet for her awakened libido, which develops to give her powers of witchcraft. The film is inspired by Jules Michelet's non-fiction book "Satanism and Witchcraft", it is the third and final film in the Animerama trilogy, and the only one to be neither written nor directed by Osamu Tezuka. (Sources: ANN, Wikipedia)

Watch Trailer

Characters

Belladonna of Sadness (1973): A Radical, Haunting Tapestry of Art, Trauma, and Rebellion

Belladonna of Sadness (Kanashimi no Belladonna), a 1973 Japanese animated film directed by Eiichi Yamamoto and produced by Osamu Tezuka’s Mushi Production, is a work that defies categorization. It is not merely an anime, nor is it simply a cult classic—it is a singular, provocative piece of cinematic art that blends beauty, horror, and social critique in ways that remain startlingly unique over half a century later. Drawing from Jules Michelet’s 1862 book La Sorcière, the film uses the allegory of witchcraft to explore themes of female oppression, power, and rebellion in a patriarchal world. Its visual and narrative audacity, combined with its unflinching depiction of trauma, make it a landmark in animation history, though its complexities demand a nuanced examination. This article delves into the film’s artistry, thematic depth, historical context, and enduring impact, offering a perspective that avoids reductive interpretations while celebrating its radical spirit.

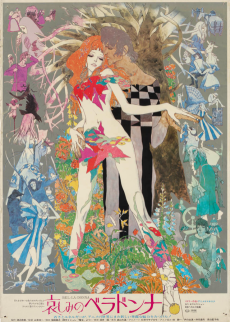

A Visual Symphony: Art Nouveau Meets Psychedelic Fever Dream

At its core, Belladonna of Sadness is a visual marvel, a film that redefines what animation can achieve. Unlike traditional anime, which often relies on fluid motion and dynamic character designs, Belladonna unfolds like a living art gallery. Its watercolor illustrations, heavily influenced by Art Nouveau and fin-de-siècle artists like Gustav Klimt, Aubrey Beardsley, and Alphonse Mucha, are both delicate and overwhelming. The film employs long, panning shots across static images, giving it the feel of a picture book brought to life. Yet, this stillness is punctuated by bursts of vivid, swirling animation—particularly during scenes of violence, transformation, or psychedelic excess—that jolt the viewer into a heightened state of awareness.

The aesthetic choices are deliberate and evocative. Jeanne, the protagonist, is rendered with sylph-like grace, her flowing lines and ethereal beauty evoking Klimt’s golden muses or Beardsley’s intricate decadence. Yet, the film’s beauty is not merely decorative; it serves as a counterpoint to its darker themes. The watercolor landscapes, with their vibrant hues and textured brushstrokes, create a dreamlike quality that contrasts sharply with the brutality of the narrative. For instance, the harrowing depiction of Jeanne’s rape is abstracted into an expressionistic sequence where her body is torn apart, a visual metaphor that conveys the visceral horror without resorting to graphic realism. This interplay of beauty and violence is central to the film’s impact, forcing viewers to confront the dissonance between aesthetic allure and narrative cruelty.

The soundtrack, composed by Masahiko Satoh, is equally integral to the experience. Its pulsating, psychedelic rock score, anachronistic for a story set in medieval France, amplifies the film’s surreal tone. Tracks reminiscent of Miles Davis’s Bitches Brew or early Pink Floyd underscore Jeanne’s descent into despair and empowerment, creating a sonic landscape that feels both timeless and disorienting. Together, the visuals and music create a sensory overload that immerses viewers in Jeanne’s fractured psyche, making Belladonna less a film to watch and more an experience to endure.

Narrative and Themes: A Complex, Flawed Allegory

The story of Belladonna of Sadness follows Jeanne, a peasant woman in medieval France who, on her wedding night, is subjected to a brutal assault by the local baron and his courtiers, enacting the feudal practice of droit du seigneur. Traumatized and abandoned by her community, Jeanne is visited by a phallic, devil-like entity who offers her power in exchange for her body and soul. As famine, war, and oppression ravage her village, Jeanne’s pact with the devil transforms her into a witch, granting her the ability to heal and destroy. Her growing power threatens the patriarchal and feudal order, leading to her eventual execution at the stake. The film concludes with a provocative coda, linking Jeanne’s rebellion to the French Revolution and female emancipation, symbolized by imagery from Eugène Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People.

On one level, Belladonna is a bold allegory for female empowerment in a patriarchal society. Jeanne’s journey from victim to witch can be read as a reclaiming of agency, with witchcraft symbolizing resistance against oppressive systems. The devil, who declares, “I am you,” suggests that Jeanne’s power comes from within, a manifestation of her suppressed rage and desire for autonomy. Her refusal of the baron’s offer to become “nobility, second only to me” and her demand for “everything” underscore her rejection of compromised power within a corrupt system. This narrative thread aligns with Jules Michelet’s view of witchcraft as a form of rebellion against feudalism and religious authority, a perspective the film explicitly draws upon.

However, the film’s feminist credentials are not without complications. Critics have noted that Jeanne’s empowerment is deeply tied to her sexuality, which is often depicted through a male gaze. Her transformation into a witch is catalyzed by sexual violence and coercion, and the film’s hypersexual imagery—particularly in scenes of orgiastic excess—can feel exploitative rather than liberating. Jeanne’s agency is undermined by the fact that her power stems from the devil’s manipulation, and her sexual experiences are rarely consensual or pleasurable. This contradiction reflects the film’s historical context: produced during Japan’s “sexual revolution” and the decline of the film industry, Belladonna was part of Mushi Production’s attempt to survive by creating adult-oriented content, including elements of pinku eiga (erotic softcore films). The result is a film that both challenges and perpetuates problematic representations of female sexuality, making its feminist message feel superficial or conflicted to some viewers.

Moreover, the characters, including Jeanne, are often more symbolic than fully realized. The film prioritizes visual and thematic impact over psychological depth, rendering Jeanne as a cipher for broader ideas rather than a fleshed-out individual. This lack of nuance can make the film’s commentary on patriarchy, class oppression, and female agency feel heavy-handed, particularly in the final sequence, which some critics have called “cringe-worthy” for its overly didactic nod to revolutionary feminism. Yet, this same lack of subtlety contributes to the film’s raw, uncompromising energy, making it a powerful, if imperfect, critique of systemic injustice.

Historical Context: A Studio’s Swan Song and a Cultural Artifact

Belladonna of Sadness was the final film in Mushi Production’s Animerama trilogy, a series of adult-oriented animated films that also included A Thousand and One Nights and Cleopatra. Produced during a period of financial turmoil for the studio, the film’s commercial failure contributed to Mushi Production’s bankruptcy in 1973. This context is crucial to understanding the film’s bold, almost desperate creativity. Facing an industry shift toward exploitation films and pinku eiga, the studio pushed the boundaries of animation to create something that could compete in a crowded, sensationalist market.

The film also reflects the cultural upheavals of the early 1970s, both in Japan and globally. The “sexual revolution” and postwar disillusionment informed its provocative imagery and themes, while its exploration of female rebellion resonated with emerging feminist discourses. However, as with many films of the era, its depiction of sexual violence as a metaphor for societal breakdown often comes at the expense of female characters, a trend seen in global cinema of the period. Despite these flaws, Belladonna stands out for its willingness to confront taboo subjects and challenge the perception of animation as a medium for children. Its rediscovery, particularly after a 4K restoration in 2016, has cemented its status as a cult classic and a touchstone for discussions about animation’s potential as an art form.

Enduring Impact and Relevance

Belladonna of Sadness is not an easy watch. Its graphic depictions of sexual violence, combined with its surreal and often disturbing imagery, require a viewer willing to engage with discomfort. Yet, its uniqueness lies in its refusal to conform to conventional storytelling or animation norms. It is a film that demands to be experienced, not just seen, and its influence can be felt in later works that push the boundaries of the medium, from Ralph Bakshi’s provocative animations to contemporary experimental films.

The film’s exploration of power, trauma, and rebellion remains relevant today. Its depiction of a woman navigating a world that seeks to control and destroy her resonates with ongoing conversations about gender, autonomy, and systemic oppression. However, its reliance on sexual violence as a narrative device raises questions about how stories of female empowerment are told and whose perspectives they prioritize. For modern audiences, Belladonna serves as both a historical artifact and a provocation, inviting reflection on how far society has come—and how far it still has to go—in addressing the issues it raises.

Conclusion: A Flawed Masterpiece

Belladonna of Sadness is a film of contradictions: breathtakingly beautiful yet deeply unsettling, fiercely rebellious yet troublingly exploitative, profoundly ambitious yet narratively uneven. It is a work that challenges viewers to grapple with its complexities, to admire its artistry while questioning its politics. As a landmark in animation, it pushed the medium into uncharted territory, proving that cartoons could be as provocative and thought-provoking as live-action cinema. For those willing to embrace its strangeness, Belladonna offers a haunting, unforgettable journey—one that lingers like the aftertaste of its namesake plant, both beautiful and dangerous.

Support Our Anime Community!

Love watching the latest anime? Help us keep uploading new episodes by join telegram channel ❤️

Join Now!